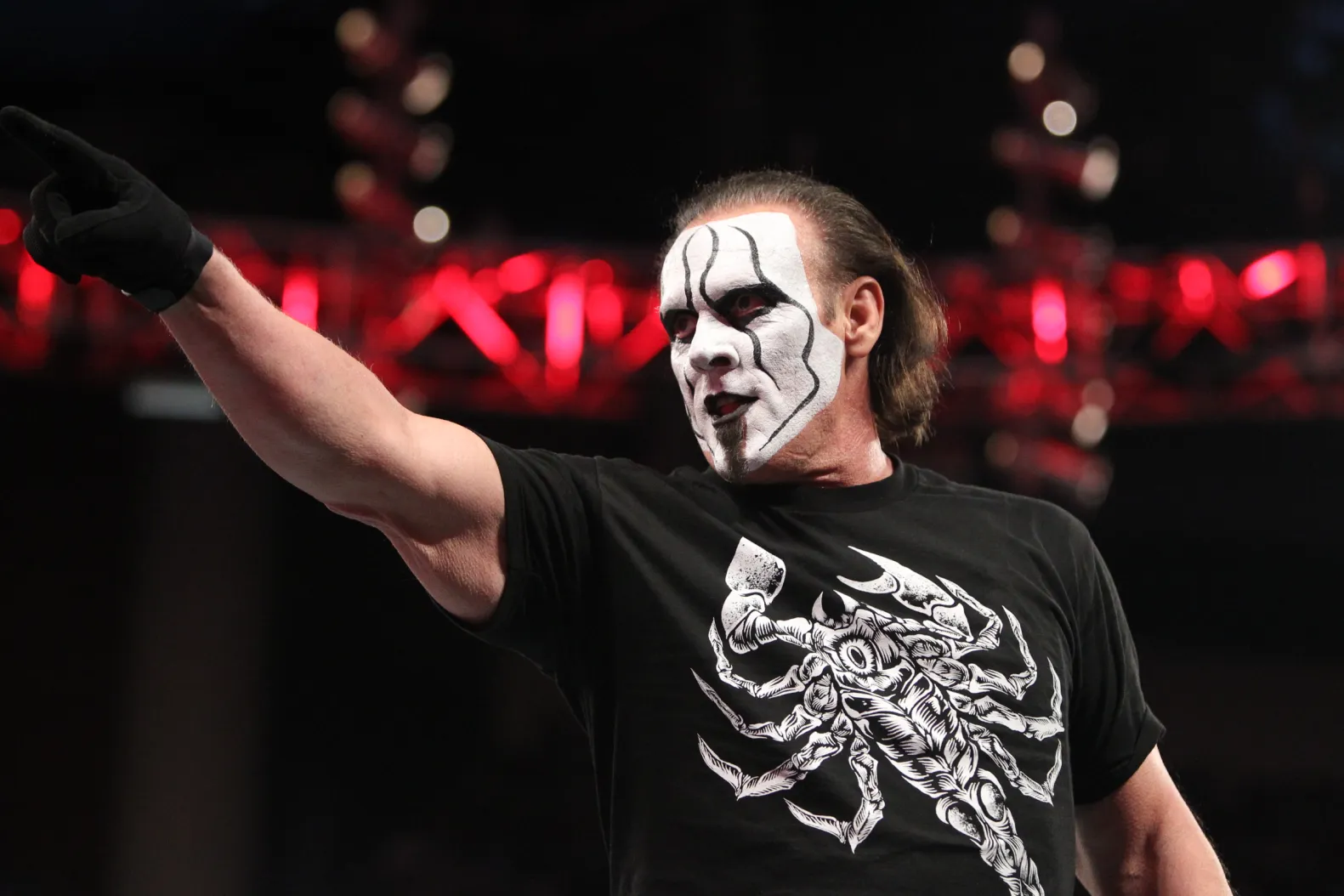

On a recent edition of his “Strictly Business” podcast, WWE Hall of Famer Eric Bischoff discussed his strategy of using nostalgia to his advantage while running WCW, and compared it to AEW tapping into Sting’s nostalgia last night at AEW Revolution 2024.

You can check out some highlights from the match below:

On how to properly tap into nostalgia: “I think AEW did a great job last night with the setup with Sting, and him coming down out of the rafters and ending up on a ramp behind the Bucks and all that. I mean, that was pure — that was such a nod to Sting, probably 1997, ’98 at really the height of the Crow character. And I think that was a really tasteful, entertaining, fun way — particularly in the context of Sting’s last match, last night was supposed to be his last Dynamite. So I think that was such a classy and entertaining kind of tip of the hat to what was, in many respects — it’s arguable, it’s all subjective — but really the peak of Sting’s success, I think was that era. Which is why we’re still seeing his character today. Which is why we saw what we saw last night, which is an homage to Sting and Nitro and all that. And again, it was very well done. It’s very entertaining.

“But there is — you have to have a balance. You know, you want to satisfy that nostalgic itch. But you don’t want to scratch it so hard you draw blood. And I think scratching it too hard would be an overabundance of it. Too — you know, if you looked at a card or you just looked at a show, forget about the card necessarily. But you just look at what’s on that show, I think it nods to nostalgia in this case. Focusing on it because it is leading to a big event. 20-25% of your show, if it’s a tasteful, entertaining, classy way to tip the hat to years gone by? I think that’s awesome. And that also satisfies the younger and newer audience, because they have a relationship to the history as well, to the legacy of performers like Sting and Ric Flair and others from that era. So yeah you’ve got to be careful, you don’t overdo it. It’s just like anything else, man.”

On whether he used nostalgia for local markets while running WCW: “In terms of what WCW did differently, you have to remember. WCW is sort of — you know, WCW originally was a part of the Crockett promotional infrastructure. So many people that were originally part of Jim Crockett Promotions, once Ted bought them out of bankruptcy [and] brought them over, created WCW, a lot of the same people that were part of the Crockett Promotions infrastructure came over. Including David Crockett, Jackie Crockett, Gary Juster. A lot of the people that were familiar with or working directly with. Elliott Murdock for example, was a local promoter. So many of them came over. So just about everything that they had been doing in that market — the relationships they had with the buildings, the venues, the building managers, the people that made the decisions — they were a very close-knit kind of community. And WCW kind of continued doing business as they always had shortly after WCW was created, meaning that WCW didn’t treat that market any differently at all. They just kind of continued what they had been doing.

“Once I came on board and started to have influence, and eventually control over live events, that market had been burned to the ground. When I got to WCW in 1991, we would go to events for my — Anderson, South Carolina. My very first television taping, I don’t think there were 800 people in the audience. That’s where that market was with WCW when I got there. Once I had control over WCW, I didn’t treat the market any differently until it became apparent that promoting live events, especially non-televised live events, was a complete waste of money and time. We were losing money every time we went out the door. I’ve said that repeatedly, and it was a fact. It wasn’t until really ’95, ’96 that we became a little more popular. And even then, I was reluctant to go to those markets in the Southeast where traditionally we had been so often, because we just overused them. We went to those markets so often, it’s like, ‘Oh, WCW is back in town.’ ‘Oh, were they just here last month?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘Did you have fun?’ ‘Eh, it was alright.’ ‘Eh, let’s go do something else.’ That was kind of the prevailing perception of the brand if you will. It wasn’t really until ’95, ’96 that that began to change. And we became pretty judicious about where we promoted, especially our bigger bands, our televised events. Then it started to change. But with respect to how much additional kind of nostalgia that we brought to the table when we went to those markets? It was never a consideration. We didn’t do anything any differently, we were just more selective about where we went and how often.”

In a recent episode of his “Strictly Business” podcast, WWE Hall of Famer Eric Bischoff discussed the use of nostalgia in professional wrestling and compared it to All Elite Wrestling’s (AEW) recent utilization of Sting’s nostalgia at AEW Revolution 2024.

Bischoff praised AEW for their tasteful and entertaining approach to tapping into Sting’s nostalgia during the event. He specifically highlighted Sting’s entrance, reminiscent of his iconic “Crow” character from the late 1990s, and how it was a classy homage to Sting’s peak success. Bischoff believes that AEW’s nod to nostalgia was well-executed and satisfying for both longtime fans and newer audiences who have a relationship with wrestling history.

However, Bischoff also emphasized the importance of finding a balance when using nostalgia. He warned against overdoing it and scratching the nostalgic itch too hard, as it could potentially alienate viewers. He suggested that dedicating around 20-25% of a show to tasteful and entertaining nods to the past is ideal. This approach allows for the satisfaction of nostalgic cravings while still appealing to younger and newer audiences.

When reflecting on his time running WCW, Bischoff discussed the differences in utilizing nostalgia for local markets. He explained that WCW initially continued the practices of Jim Crockett Promotions, which included maintaining relationships with venues and promoters in specific markets. However, when Bischoff took control of WCW in 1991, he realized that many markets had been overused and were no longer drawing significant crowds.

Bischoff made the decision to be more selective about where WCW promoted events, especially non-televised ones, as they were losing money and time. It wasn’t until 1995-1996 that WCW began to regain popularity and became more judicious about their market choices. Bischoff noted that during this time, they focused on bigger events and televised shows. However, he clarified that WCW did not prioritize bringing additional nostalgia to these markets; their main focus was on selecting the right venues and promoting events strategically.

Overall, Bischoff’s insights shed light on the importance of nostalgia in professional wrestling and how it can be effectively utilized without overwhelming the audience. A tasteful and balanced approach to tapping into nostalgia can create memorable moments while still appealing to a wide range of fans.